Turning random encapsulation into predictable single-cell control

Single-cell droplet microfluidics enables millions of parallel experiments, yet reliably loading exactly one cell per droplet remains a statistical challenge. This article explains why random encapsulation follows Poisson limits, what this means in practice, and how modelling, visualisation tools, and smart microfluidic design can turn uncertainty into predictable, controlled single-cell workflows.

Single-cell analysis has transformed how scientists study biology. Instead of averaging signals across millions of cells, researchers can now observe how individual cells behave, interact, and respond differently to the same environment. This shift has revealed profound cellular heterogeneity that bulk methods simply cannot capture.

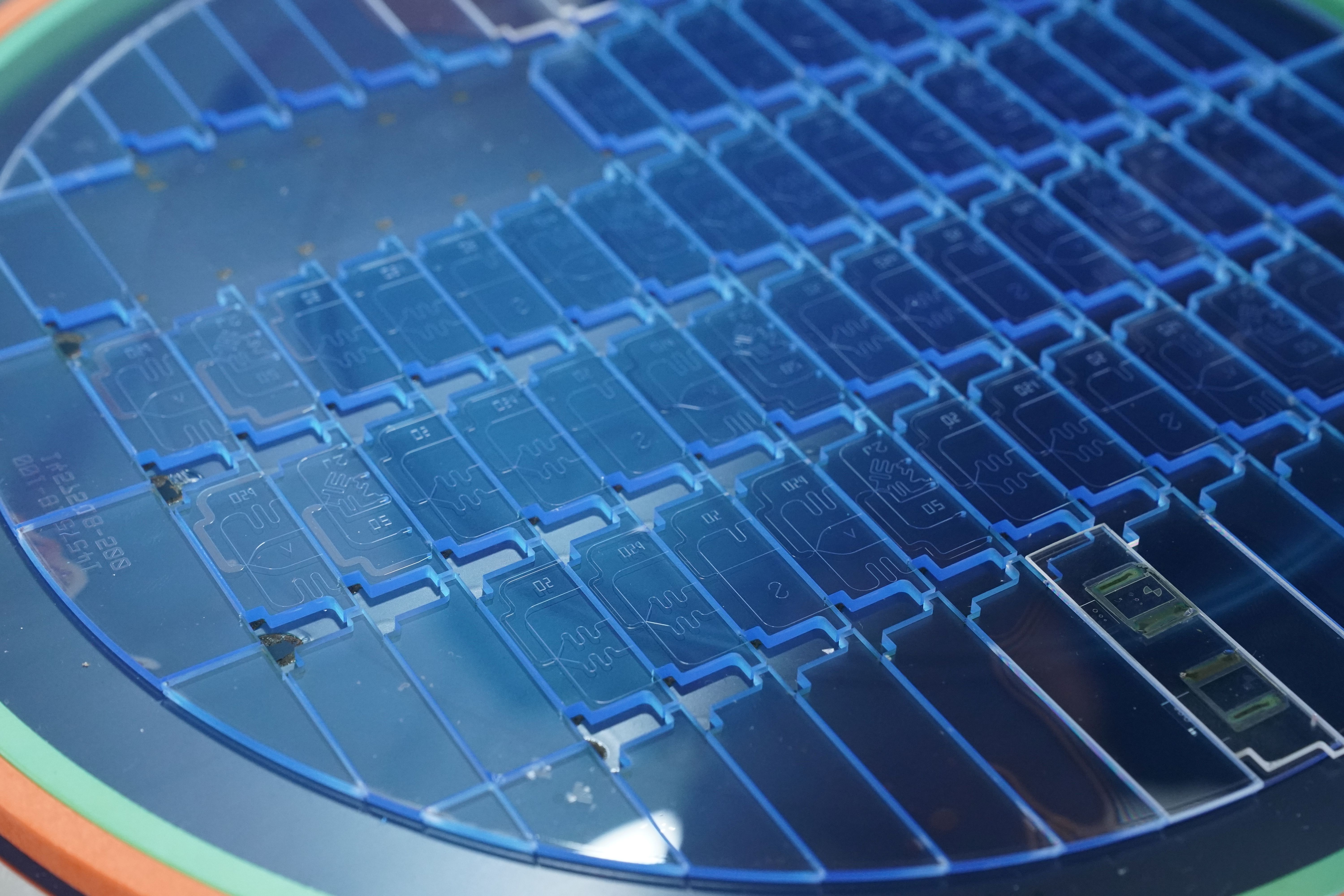

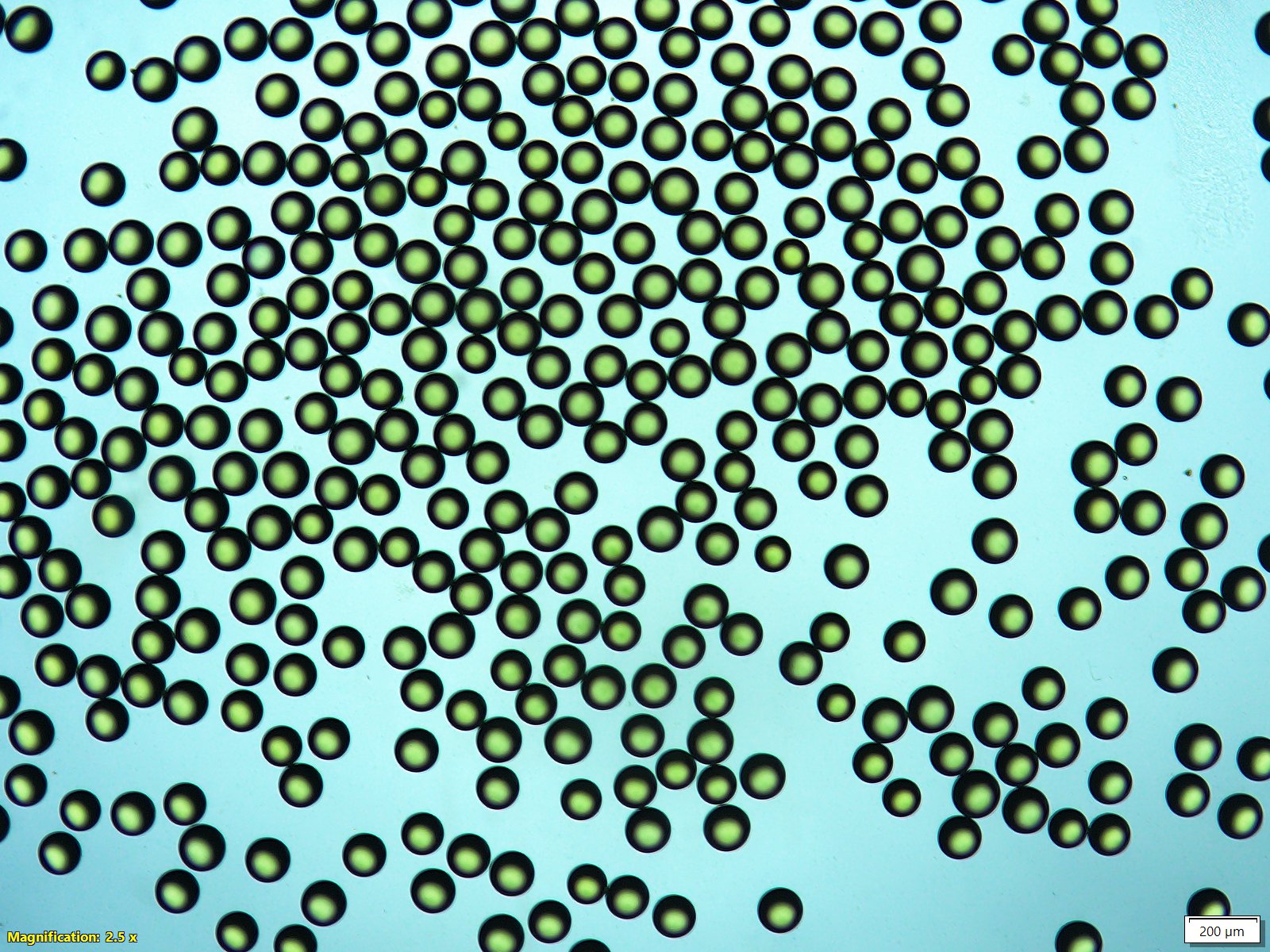

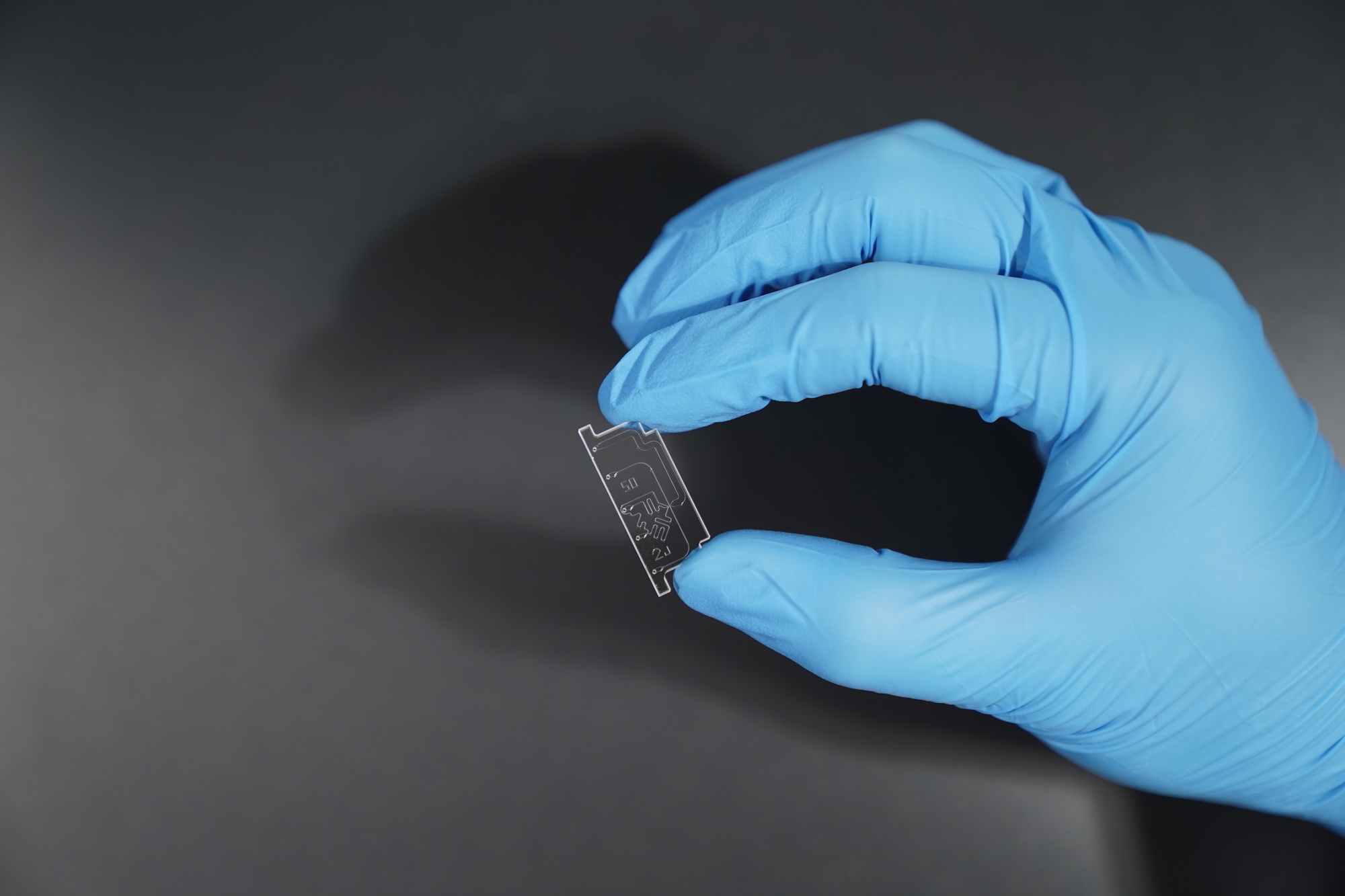

Droplet microfluidics has become one of the most powerful technologies enabling this shift. By generating thousands to millions of uniform droplets per experiment, each droplet acts as a tiny, isolated reaction chamber. In principle, this makes it possible to run millions of single-cell experiments in parallel.

In practice, however, there is a persistent challenge:

How do you reliably put exactly one cell into each droplet?

1. Why is single-cell encapsulation harder than it seems?

In a typical droplet microfluidic system, cells are suspended randomly in an aqueous phase. As droplets form at a junction (whether a T-junction, co-flow, or flow-focusing geometry), each droplet simply captures whatever cells happen to be present in that tiny volume at that exact moment.

There is no active selection, no timing, and no guarantee. As a result:

- Many droplets contain no cells

- Some contain one cell

- Others contain two or more cells

Even in perfectly stable microfluidic systems, this randomness cannot be eliminated. It is a statistical property of how particles distribute in small volumes.

2. The Poisson distribution: The hidden rule of droplet loading

Passive single-cell encapsulation in droplet microfluidics follows the Poisson distribution, a model describing the probability of random events occurring within a fixed volume. In this case, the “events” are cells entering droplets.

The distribution depends on a single parameter, λ (lambda), which represents the average number of cells per droplet. The probability of a droplet containing k cells is given by:

Poisson statistics tell us the probability that a droplet contains 0, 1, 2, or more cells based solely on λ. While the underlying equation is simple, its consequences are profound.

Most importantly: Even under ideal Poisson loading, single-cell droplets are never the majority. At λ = 1, only ~37% of droplets contain exactly one cell [1], but this is accompanied by ~18% of droplets containing two cells, and ~8% containing three or more cells. Lowering λ reduces doublets, but at the cost of producing mostly empty droplets.

To reduce doublets, researchers often lower cell concentration, accepting that most droplets will be empty and that precious samples and reagents will be wasted. This statistical ceiling is not a design flaw; it is a mathematical consequence of random encapsulation.

3. Making Poisson statistics tangible: a real example

Statistics become much clearer when we look at real numbers.

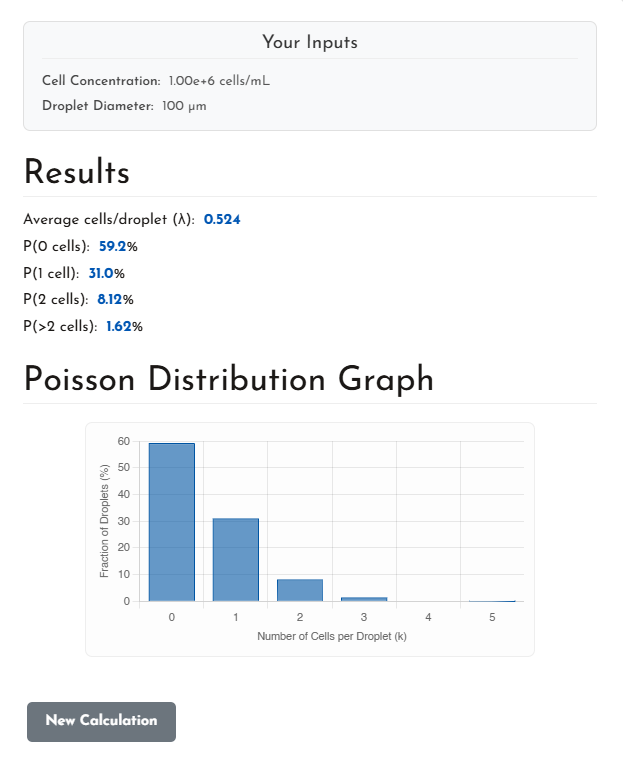

Below is an example output from the Blacksheep Sciences (BSS) Poisson Distribution Calculator, using parameters that are common in many droplet experiments:

- Cell concentration: 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL

- Droplet diameter: 100 µm

From these inputs, the calculated average loading is:

λ = 0.524 cells per droplet

This is a conservative operating point, well below λ = 1, chosen specifically to reduce doublets.

What does this mean in practice?

At λ = 0.524, the predicted droplet population breaks down as follows:

- Empty droplets (P(0)): ~59%

- Single-cell droplets (P(1)): ~31%

- Two-cell droplets (P(2)): ~8.1%

- Droplets with >2 cells: ~1.6%

In other words:

- Nearly two-thirds of droplets are empty

- Only about one-third contain a single cell

- Almost 1 in 10 droplets contains two or more cells

This is a textbook example of Poisson-limited encapsulation. Even with cautious cell loading, doublets remain present, and efficiency is inherently limited.

Why this visualisation matters?

For experimental workflows, these percentages have direct consequences:

- Empty droplets reduce effective throughput and increase reagent and sequencing costs

- Doublets introduce ambiguity and often require downstream filtering

- Single-cell yield determines how many droplets must be generated to reach a usable dataset

By visualising these outcomes in advance, researchers can move beyond intuition and make informed design decisions.

Tools like the BSS Poisson calculator do not replace theory. They make it actionable, allowing teams to quickly explore “what-if” scenarios before committing samples and time.

4. Engineering ways to push beyond Poisson limits

While Poisson statistics describe passive encapsulation, the field has developed many strategies to push beyond random loading.

Researchers have developed several strategies to shift outcomes closer to deterministic single-cell loading:

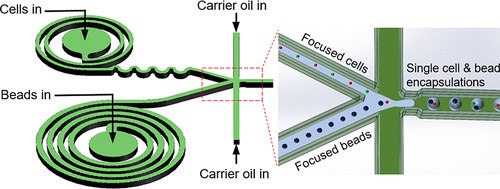

4.1. Passive ordering techniques

Methods such as inertial focusing and Dean flow in spiral channels hydrodynamically order cells before droplet formation. By spacing cells more evenly, single-cell encapsulation efficiencies above 80% have been reported under optimized conditions [1,2]

On-chip enrichment: Recent work demonstrates that removing excess carrier fluid after cell ordering can locally increase effective cell concentration without introducing excessive cell–cell interactions. This allows significantly higher single-cell encapsulation efficiencies (up to 80%) than predicted by Poisson statistics alone [3].

However, these methods often require:

- High cell concentrations

- Long channels

- Careful flow control

4.2. Active encapsulation techniques

Active methods synchronize droplet generation with cell detection using electrical, optical, acoustic, or mechanical triggers. These approaches can achieve near-deterministic encapsulation but at the cost of:

- Lower throughput

- Higher system complexity

- Potential impacts on cell viability

As a result, Poisson-limited encapsulation remains widely used due to its simplicity and robustness.

5. Why Poisson statistics still matter?

Despite newer techniques, Poisson-limited encapsulation remains widely used because it is:

- Simple and robust

- Highly scalable

- Compatible with many cell types

- Easy to predict and model

Understanding Poisson behaviour allows researchers to design experiments intelligently, interpret results honestly, and decide when added complexity is truly justified.

6. From randomness to predictability

Single-cell droplet microfluidics will always involve an element of chance—but it does not have to involve guesswork.

By combining:

- A clear understanding of Poisson statistics

- Visual planning tools

- And smart microfluidic design

Researchers can turn random encapsulation into a predictable, quantifiable process.

In single-cell science, a little bit of math goes a long way, not by eliminating randomness, but by helping us work effectively with it.

References:

[1] Ling, S.-D.; Geng, Y.; Chen, A.; Du, Y.*; Xu, J. Enhanced single-cell encapsulation in microfluidic devices: From droplet generation to single-cell analysis. Biomicrofluidics, 14, 061508 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0018785

[2] Li, L.; Wu, P.; Luo, Z.; Wang, L.; Ding, W.; Wu, T.; Chen, J.; He, J.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; He, L. Dean flow assisted single cell and bead encapsulation for high performance single cell expression profiling. ACS Sensors, 4, 1299–1305 (2019). https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssensors.9b00171

[3] Tang, T.; Zhao, H.; Shen, S.; Yang, L.; Lim, C. T. Enhancing single-cell encapsulation in droplet microfluidics with fine-tunable on-chip sample enrichment. Microsyst Nanoeng 10, 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-023-00631-y

.JPG)