Choosing materials for microfluidic chips: Glass, polymers, and emerging platforms

In this post, we dive deep into comparing the pros and cons of the most popular substrates—from the precision of glass and the flexibility of PDMS, to scalable polymers like COC and PMMA—to help you avoid common material selection pitfalls in your chip development journey.

Before diving into the details, the table below provides a quick comparison of the most important properties across glass, PDMS, and thermoplastic materials—helping you immediately see how each option stacks up.

Quick comparison of common microfluidic materials:

Microfluidics has unlocked incredible possibilities, from advanced medical diagnostics to complex chemical synthesis. But as you start your design, you face one critical, foundational question: How do you choose the right material for your microfluidic chip? This decision doesn't just define the device's structure; it dictates chemical compatibility (solvent resistance), optical clarity, and, crucially, whether your device can smoothly transition from a PDMS prototype in the lab to commercial production using thermoplastics.

In this post, we dive deep into comparing the pros and cons of the most popular substrates—from the precision of glass and the flexibility of PDMS, to scalable polymers like COC and PMMA—to help you avoid common material selection pitfalls in your development journey.

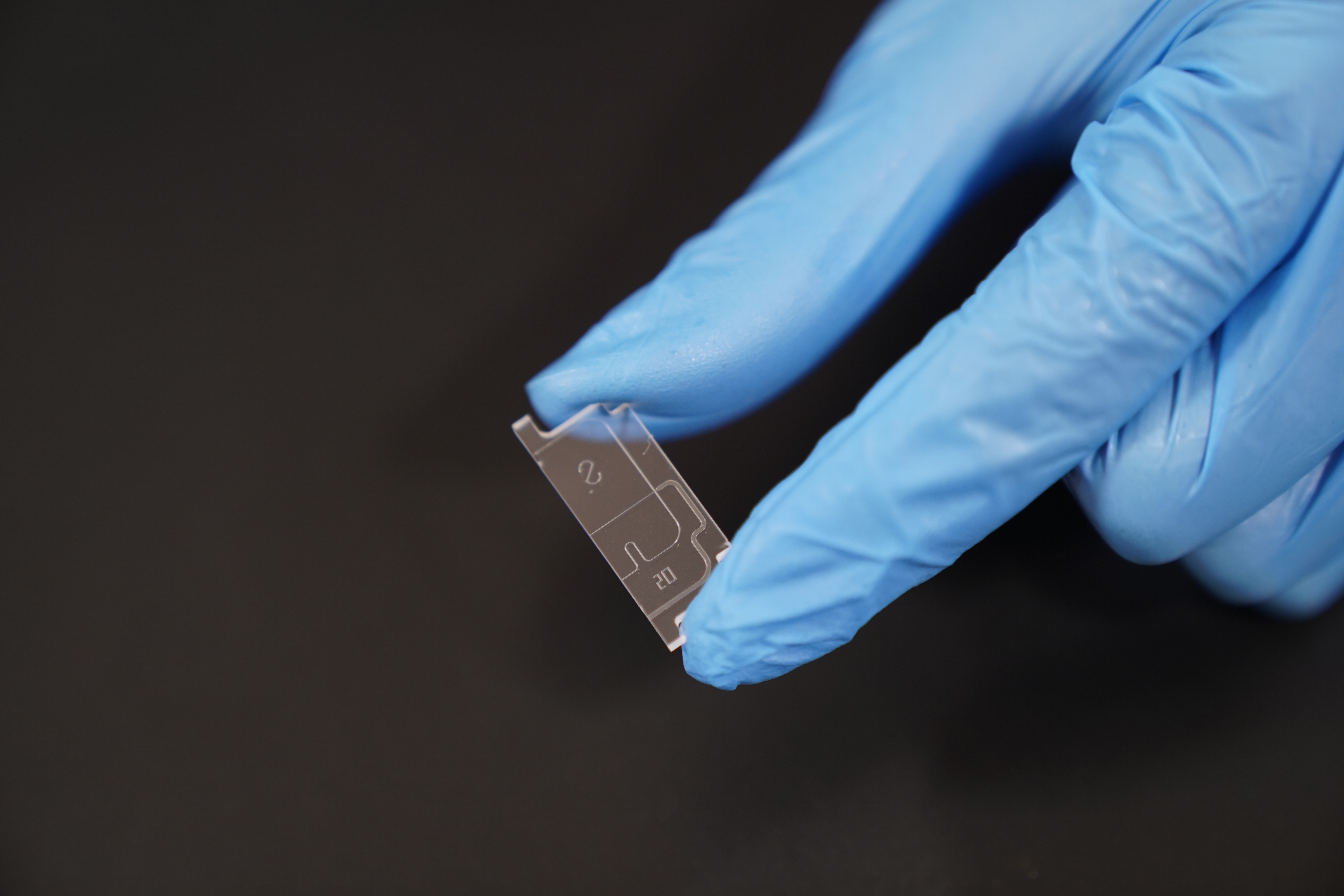

Glass: The gold standard for precision and chemical resistance

For years, glass was the default substrate for microfluidics, and for good reason. It offers excellent optical transparency, making it ideal for fluorescence imaging, microscopy, and high-precision detection methods. Its chemical resistance is unmatched among common microfluidic materials, allowing it to be used with organic solvents, acids, high-ionic-strength buffers, and surfactants.

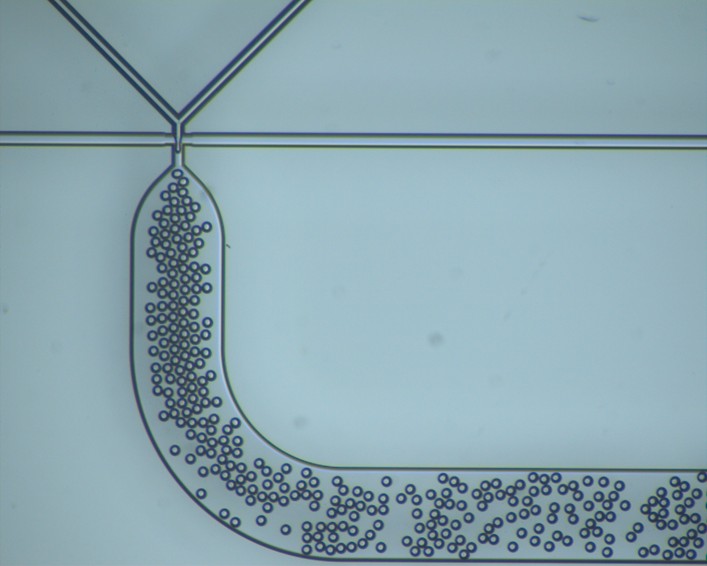

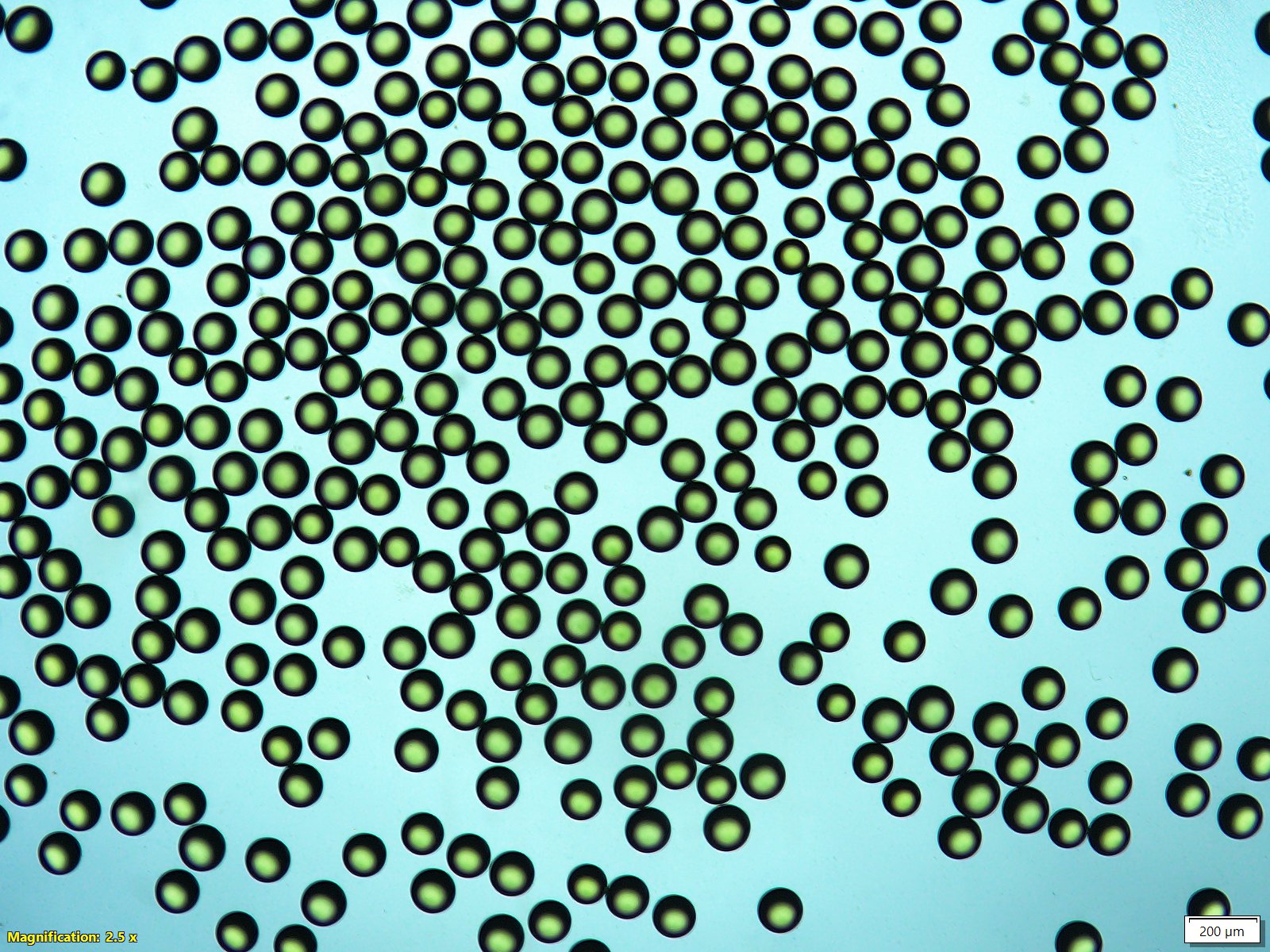

Beyond its chemical advantages, glass provides mechanical rigidity, allowing devices to withstand high pressures without deformation. This makes it especially useful for droplet microfluidics, chromatographic microspheres, high-pressure chemical reactors, and electrokinetic systems.

Fabrication typically involves techniques such as wet etching or laser ablation, followed by thermal or anodic bonding. While this yields exceptional performance, the trade-off is cost: glass chips require clean-room equipment, specialized microfluidic fabrication techniques that require skilled operators, and longer lead times. Additionally, glass is brittle, so handling and device packaging must be performed with care.

If your application demands solvent resistance, optical precision, and long-term reliability, glass is the ideal choice. It may not enable the fastest prototyping, but it sets the performance ceiling that other materials strive to match.

Elastomers and PDMS: Rapid prototyping and research freedom

PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) is one of the defining materials of modern microfluidics, with its popularity stemming from the simplicity of its fabrication, particularly through soft lithography. A single mould can produce high-quality PDMS devices in just a few hours, making it extremely friendly for academic laboratories and early-stage research.

PDMS offers optical transparency, flexibility, gas permeability (great for cell culture), and low cost. These features make it the favourite choice in academia for organ-on-chip systems, droplet generation experiments, and new microfluidic concepts. For example, Emulate Bio uses a PDMS-based organ-on-chip platform to model organ-level physiology for drug research.

However, its limitations are equally important. PDMS absorbs small hydrophobic molecules and swells in many organic solvents such as toluene or hexane. It is also challenging to scale for large-volume or industrial manufacturing. Surface treatments that make it hydrophilic fade over time, and manual fabrication methods don’t translate well into high-volume production.

While PDMS excels in speed and flexibility during development, it is less suited for large-scale manufacturing. For that reason, many projects begin with PDMS prototypes and later transition to rigid polymers.

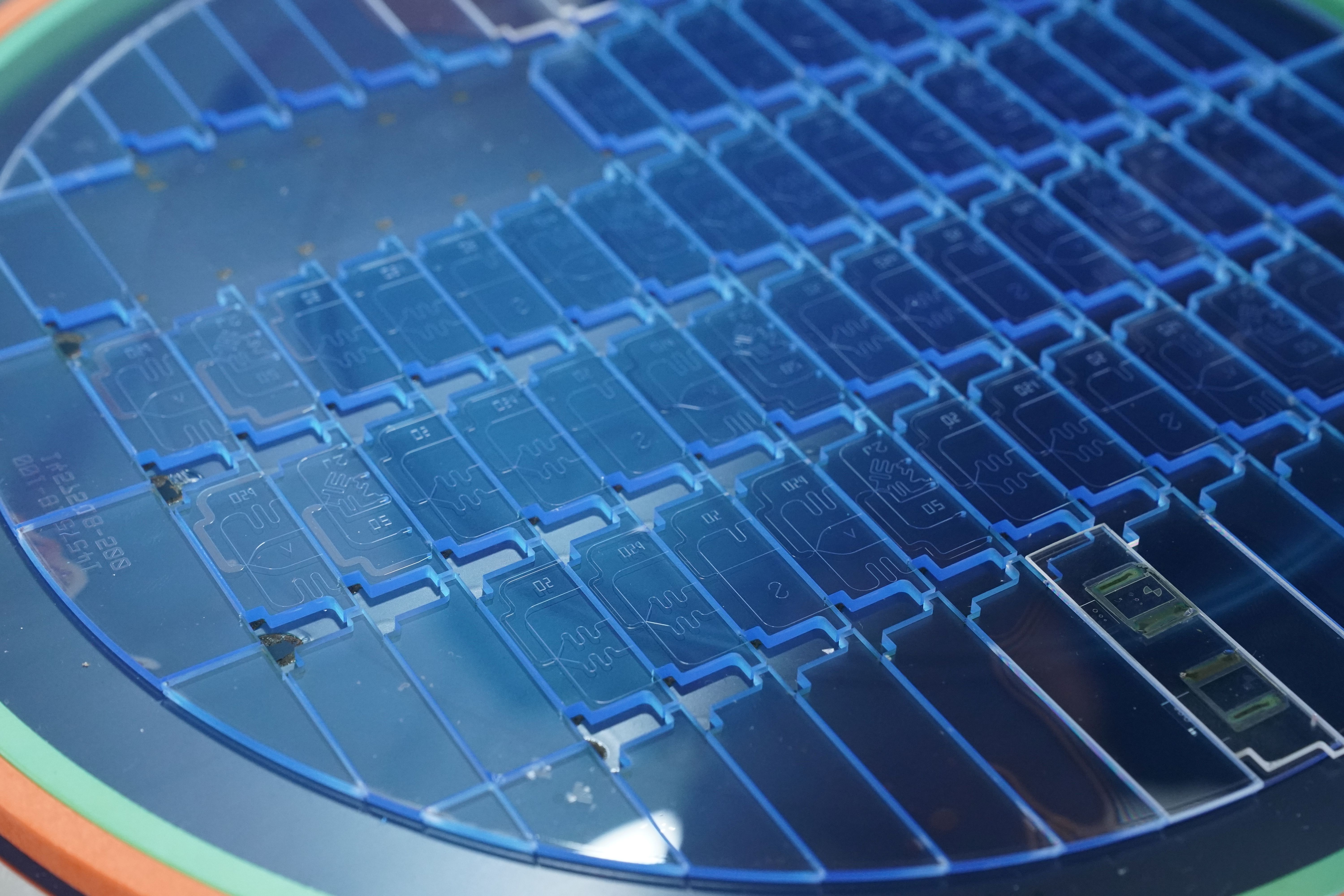

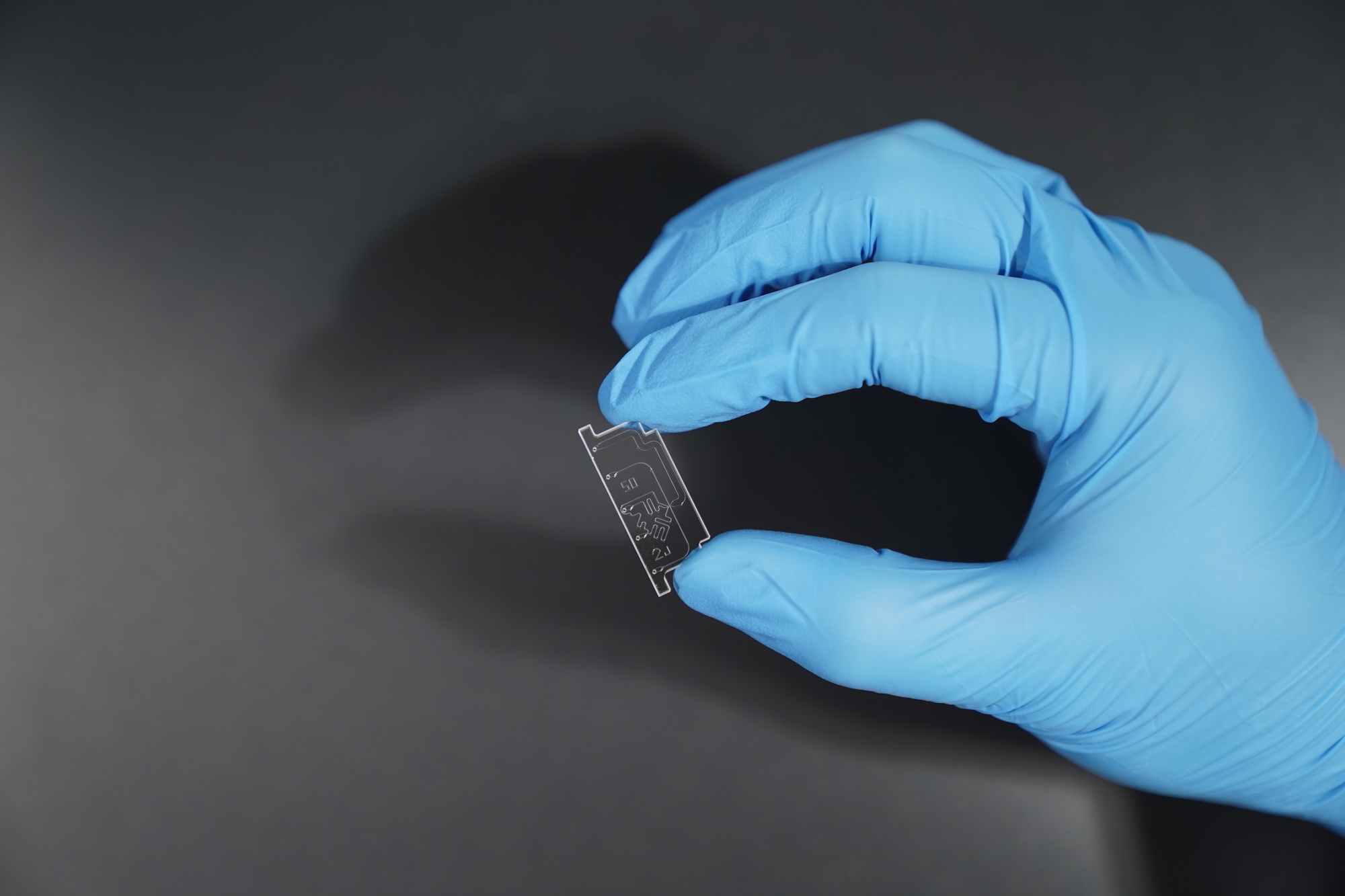

Thermoplastics: Bridging prototype and production

When a microfluidic design moves toward commercialization, thermoplastics such as PMMA (Poly Methyl Methacrylate), COC (Cyclic Olefin Copolymer), PC (Polycarbonate), and PS (Polystyrene) become the materials of choice.

These plastics are compatible with injection-moulding or hot-embossing, enabling high throughput and low cost per chip at scale. They typically provide good optical transparency, mechanical strength, and tailored surface modification options. For example, COC stands out in diagnostic cartridges thanks to its low autofluorescence, moisture resistance, and optical clarity.

However, thermoplastics are not perfect. Their resistance to aggressive solvents can vary, and the initial tooling investment for mould fabrication can be substantial, making them less ideal for early-stage iteration. Achieving precise bonding and a smooth surface finish can be more challenging compared to PDMS. Additionally, thermal bonding carries the risk of channel collapse, particularly in small or shallow microchannels.

Nevertheless, for applications where manufacturability, cost, and mechanical stability are key, thermoplastics often represent the most efficient path forward.

Emerging materials: Expanding the toolbox

The material landscape of microfluidics is not static. As microfluidics expands into softer biological systems, more aggressive chemistries, and cost-sensitive diagnostics, engineers and scientists are looking beyond traditional materials and embracing innovative new options.

Fluoropolymers (PTFE - polytetrafluoroethylene, FEP - fluorinated ethylene propylene, PFA - perfluoro alkoxy) deliver superb chemical and solvent resistance, making them ideal for droplet microreactors using fluorinated oils or organic reagents. Silicon, long the domain of microelectronics, offers integration with sensors, precise thermal control, and high durability. Hydrogels and paper-based substrates unlock low-cost, disposable, and biomimetic platforms. And 3D-printed resins are enabling rapid iteration of complex geometries that were previously impossible.

These materials won’t replace glass, PDMS or thermoplastics overnight, but they expand what’s possible for microfluidic designers.

From prototype to production: Material transitions matter

One of the most common pitfalls in microfluidic development is assuming the material choice at the prototype stage can remain unchanged in production. Changes in surface energy, bonding method, or mechanical stiffness can subtly—but critically—affect droplet formation, channel flow, or device reliability.

For example, a device designed in PDMS might generate perfect droplets at the bench, but when re-fabricated in COC, the same flow rates give a different droplet size or regime shift. To avoid this, many developers now choose prototyping materials that closely mimic their final production substrate, or plan material transitions early in the design cycle.

Key considerations include changes in surface wettability, bonding method (plasma vs thermal), shrinkage from moulding, and regulatory compliance around biocompatibility and stability.

Matching materials to your application

Rather than searching for a “one-size-fits-all” material, it’s better to match the substratum to your application. For example:

- Droplet generation with organic solvents → Glass or solvent-resistant fluoropolymer.

- Cell culture or organ-on-chip → PDMS, glass or hydrogel.

- Disposable diagnostic cartridge → COC, PMMA or PS.

- Sensor integration or thermal cycling (PCR) → PC or COC.

- Low-cost field diagnostics → Paper, fabric or hybrid systems.

Selecting the right material from the start can avoid redesigns, delays and reproducibility issues.

Looking ahead: What’s next in microfluidic materials

The future of microfluidics is material-driven. Hybrid systems—glass channels with polymer lids or coated plastics for solvent resistance—are becoming more common. Smart coatings are bringing plastics closer to glass in robustness, while 3D printing is lowering the barrier to custom geometries. Biodegradable polymers are paving the way for more sustainable devices, and integration with electronics, sensors and actuators is pushing the envelope.

Ultimately, the “best” material is the one you choose early, with a clear path to your application and scale.

.JPG)